Timeless Traditions: A Journey Through Kyoto and Echizen’s Artisanal Craft Industry

Last update

Japan is famous for its crafts and meticulous manufacturing processes. From silk dyeing to lacquerware, these industries keep old traditions alive while ensuring their relevance for today’s generation. Through their dedication and precision, artisans all over Japan are preserving Japan’s cultural heritage while adapting the crafts to the modern world.

Kyoto and Echizen are two remarkable regions that have between them a vast array of culture to be discovered, and they provide many great examples as to how the Japanese traditional arts and crafts industry is being preserved as Japan’s cultural heritage, as well as how artisans have adapted to the modern world.

While Kyoto is known for its centuries-old artistry and has remained important to fine craftsmanship, Echizen, with its long-standing rural traditions, is home to some of the country’s most exceptional paper, lacquerware, and knife-making industries. Both regions highlight the diversity and timeless appeal of Japan’s handmade treasures.

Both regions' traditional crafts undoubtedly possess diversity and timeless appeal, but it is not just the traditions that have been passed down; they have also evolved to meet the needs of the times.

The Textiles and Fabric Industry in Kyoto

Kyoto is known for its rich cultural heritage, with beautiful textiles and intricate craftsmanship among its most notable features. The city’s artisans are famous for producing some of the best traditional garments and accessories.

One tradition that stands out is Yuzen silk dyeing (友禅染), a technique created by the famous artist 友禅斎 (Yūzen-sai), who is credited with developing this style during the 17th century. Unlike regular silk dyeing, which may use stencils or printing, Yuzen is a hand-painting process where artisans carefully apply colorful designs to the fabric, often inspired by nature. This technique results in vibrant, one-of-a-kind kimonos that resemble wearable art.

Another example of Kyoto’s dedication to traditional beauty is tsumami zaiku (つまみ細工), delicate hairpins made from folded fabric. These hairpins, crafted from silk or cotton, are formed by pinching small squares of fabric into intricate shapes, creating flowers and other designs. Tsumami zaiku has a long history in Japan. Originally, they were actually made from kimono scraps and other things that could be created easily at home.

Visitors can experience these traditional crafts up close and learn more about Japan’s textile industry at several notable stores in Kyoto. Here, they can see artisans at work and even try to create their own piece.

Chiso Main Store (千總本店) (Kyoto city, Chukyo ward, Kyoto)

Chiso’s kimonos are treasured for their elegance, and the store is an essential stop for those looking to learn more about the traditional Japanese fashion and textile industry.

The store was founded in 1555 and has since built a reputation for producing the most beautiful silk kimonos in Kyoto, featuring intricate patterns and designs. Today, the store is showcasing the art of Yuzen silk dyeing: Visitors can learn about the methods behind each piece and observe some of the most elegant items inside the store’s showroom. In addition to the retail space, Chiso features an exhibition where visitors can get a closer look at the history and techniques of this industry.

Oharibako (おはりばこ) (Kyoto city, Kita ward, Kyoto)

Oharibako specializes in the creation of tsumami zaiku, delicate hairpins made by folding fabric into beautiful shapes, such as flowers. These colorful hairpins are often worn during special occasions like weddings or festivals and you may see them when women wear kimono and style their hair for these events.

At Oharibako, visitors can not only watch artisans create these hairpins but also participate in a hands-on workshop, where they can make their own tsumami zaiku.

ATELIER JAPAN a Traditional Handcraft Shop at Kyoto Station (Kyoto City, Shimogyo Ward, Kyoto)

This store was opened at Hotel Granvia Kyoto, located at Kyoto Station. Their mission is to be a base for promoting Japanese culture to the world and be a platform to promote Kyoto’s (and Japan’s overall) craftsmanship. They are not only focused on appealing to local residents but also to domestic and international visitors, expanding into next-generation lifestyles and new markets.

Watch the making of traditional Japanese sweets up close at Tsuruya Kichinobu (Kyoto City, Kamigyo Ward, Kyoto)

Founded in the third year of the Kyōwa era (1803), this long-established wagashi (Japanese sweets) shop offers a unique experience at its Kayu Chaya on the second floor. Here you can enjoy a “see and taste” experience, where you can watch a wagashi artisan’s live demonstration and listen to explanations about the art of confectionery, all while savoring seasonal fresh sweets paired with tea. You’ll also have the opportunity to ask the artisan questions directly, allowing you to gain a deeper understanding of the world of Kyoto-style wagashi.

Nanzenji Sando Kikusui A special lunch while observing traditional landscaping techniques (Kyoto City, Sakyo Ward, Kyoto)

Kikusui is a Kyoto cuisine restaurant and ryokan located on the eastern side of Kyoto, near Nanzenji Temple. The garden, which occupies about half of the property, was designed by the 7th-generation Ogawa Jihei, who is said to be the pioneer of modern Japanese gardens,and stands as a testament to the impressive art of Japanese Landscaping. You can enjoy seasonal Kyoto cuisine while overlooking the immaculate garden. The establishment offers kaiseki (traditional Japanese course meals) that incorporate both Japan’s ancient traditions and new innovations, as well as Kyoto-style Italian dishes made with seasonal ingredients from the terroir of the Kyoto region.

Washi Paper and Lacquerware in Echizen

Echizen, located in Fukui Prefecture, is known for its long-standing history of craftsmanship, particularly its paper-making, lacquerware, and bladesmith industries, which have been integral to the region for many years.

Here, visitors can enjoy a different side of Japan, only an hour away from Kyoto, and experience the exceptional skill and cultural heritage that define Echizen's craft industry, which is still thriving today.

Echizen's paper-making and lacquerware industries have been vital to the development of Japanese culture. The art of washi (和紙) paper-making, practiced for over many years, is one of Japan’s oldest and most revered traditions. Known for its durability and delicate texture, washi has played an essential role in everything from calligraphy to printmaking. Urushi (漆), or lacquerware, has similarly deep roots in Japanese history, with its glossy finish and durability making it ideal for both functional and decorative items.

Experience Making Handmade Japanese Paper at Yanase Ryōzō Paper Mill (柳瀬良三紙業) (Echizen City, Fukui)

Yanase Ryōzō Paper Mill is a great place to experience the art of washi paper-making. Echizen’s washi paper is known for its durability, unique texture, and beauty. It is often used in other industries, such as calligraphy and bookbinding.

At the mill, visitors can not only learn about the skill-intensive process of making washi by hand but also join a workshop to try making their own sheets of washi, which they can take home as a souvenir.

Experience Painting on Echizen Lacquerware at Urushi no Sato Hall (Sabae City, Fukui)

At Urushi no Sato Hall, you can learn more about the traditional Japanese lacquerware industry. Visitors can watch artisans at work and participate in workshop experiences where they can try decorating their own pieces of lacquerware.

The lacquer used in Japan is called urushi, which is derived from the sap of the urushi tree. Known for its durability and glossy finish, urushi lacquer is highly valued for both functional and decorative items, and its use in Japan dates back over 1,500 years. The technique is unique to Japan and continues to play an important role in its cultural and artistic heritage.

Here, you can not only view an exhibition of lacquerware, but also watch live demonstrations of lacquerware made by traditional craftsmen. Additionally, you can participate in a painting experience where you can decorate your own lacquerware. (Reservations required for groups of two or more, and other experiences are also available.)

Shitsurindo (Sabae City, Fukui)

Since its founding in the 5th year of the Kansei era (1793), Shitsurindō has continued to be a pinnacle of Echizen lacquerware, preserving and passing down its techniques to this day.With a commitment to both beauty and durability, Shitsurindō continues to create lacquerware without cutting corners. This unwavering dedication is the enduring pride of Shitsurindō. In the store, they offer four experiences: shopping, a showroom, workshops, and workshop tours.You can see, touch, and experience everything firsthand.

Aisomo Cosomo is an extension created in 2010 with the idea of making lacquerware more accessible for younger generations. This colorful urushi (lacquerware) is designed to complement both Japanese and Western cuisines so it can look good at any dinner table and any type of cooking. It is easy to use even for those handling lacquerware for the first time.

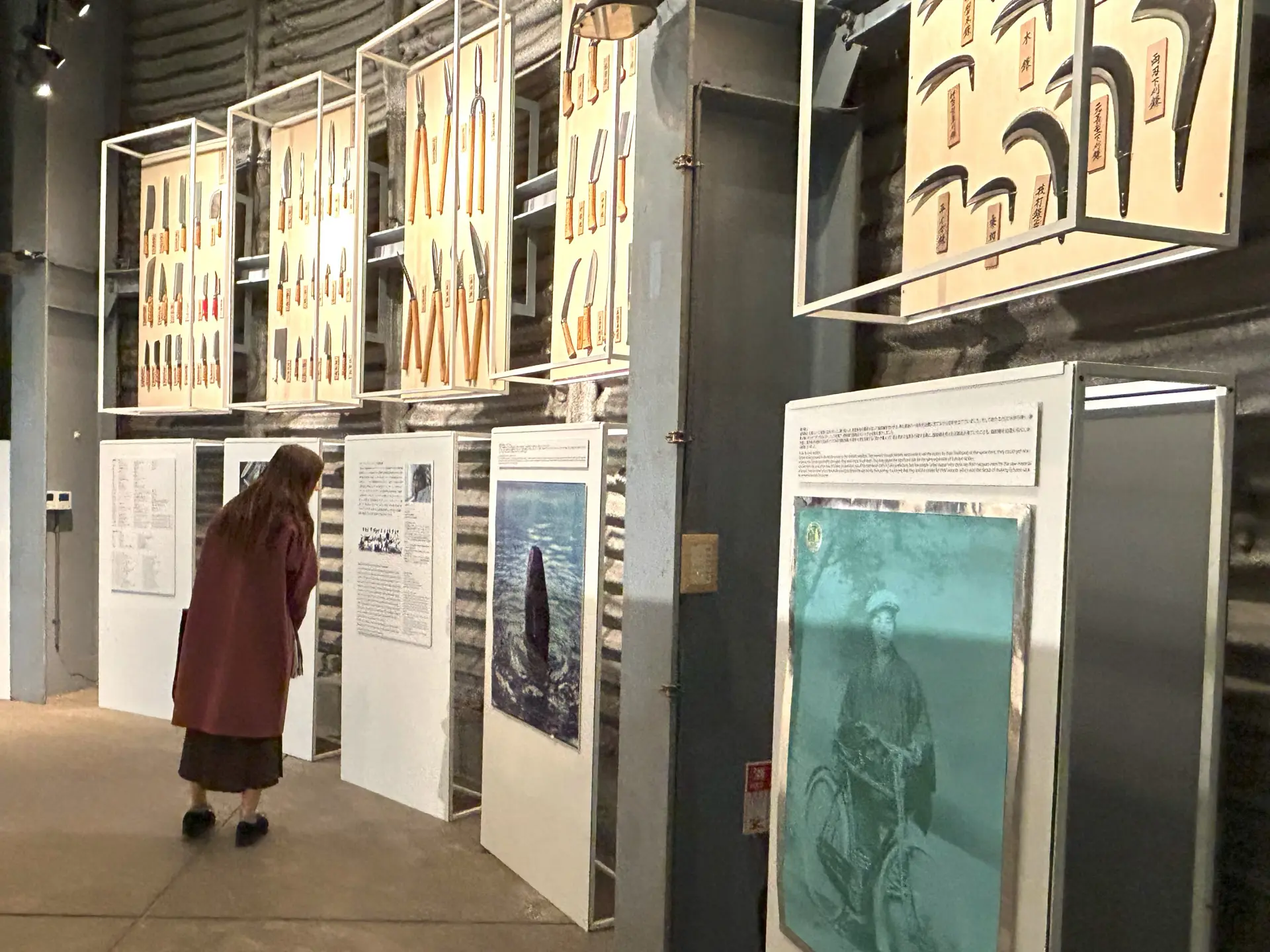

Cutting-Edge Knife Craftsmanship

Echizen is also home to one of Japan’s most renowned crafts: the manufacturing of knives. Japanese knives are well known around the world for their quality. Originally, it started with the production of farming tools which were sold while walking around. Over time, the technique of making knives developed and has been passed down to the present day, especially in the town of Takefu, where blacksmiths have been forging knives for centuries. The quality of the blades made here is exceptional, and the process of creating them remains largely unchanged from traditional techniques.

Observe the Work of a Knife Craftsman at Takefu Knife Village (Echizen City, Fukui)

Takefu Knife Village is the center of Echizen’s knife-making industry, where visitors can witness skilled bladesmiths forge traditional knives using ancient techniques passed down through generations. Individual businesses are working together to preserve these precious skills.

Visitors can watch artisans craft knives from start to finish, from heating the steel to sharpening the blade, as well as participate in hands-on experiences where they can forge their own knife with the help of skilled blacksmiths. Takefu Knife Village is a great place to gain insight into the centuries-old art of knife-making and even take home a practical yet meaningful piece of Japanese craftsmanship.

Kyoto and Echizen’s Artisanal Craft Industry Today

Artisans across Japan continuously strive to preserve the rich traditions that define the country’s cultural identity. In both Kyoto and Echizen, these artisans are leading the way, ensuring that centuries-old techniques are not only maintained but also adapted to meet the demands of the modern world.

By offering hands-on experiences, collaborating with contemporary fashion designers, and promoting their crafts online, they ensure that younger generations remain connected to their heritage. In many ways they are taking active steps to pass on their knowledge while breathing new life into this age-old crafts industry.

Check also...

Japan’s Traditions and Craftsmanship meet in Osaka: A Journey Through the Evolution of Famous Industries

Learning and Discovering with your Family: A fun, Interactive adventure in Kansai

Timeless Culture: A Journey to See, Taste, and Experience the Depth of Traditional Industries in Osaka and Nara

Exploring the Roots of Festivals: A Journey of Understanding Local Bonds and the Preservation of Culture

A 3-Day Journey Along the Path of History and Culture: Outlining the Saigoku Kaidō from Osaka

Shiga: Days Steeped in Nature and Blessed Waters Along Lake Biwa

Tottori: A Journey to Unwind in the Majesty of Nature at San’in Kaigan Geopark